Technology Management Management Conflict

Managing Professional Conflict in the Workplace

Posted on .I was recently answering a couple questions about this for someone and I found I had a lot to say about it, so I'm going to try to encapsulate those thoughts in a blog post.

I've realized it's much more important to encourage people to solve their own problems. It's what most people want, anyway. Your job is to listen to them and to give them tools and encouragement they need. My first answer to 'Professional Conflict in the Workplace' - is that youneed to help people help themselves. It took me a long time to figure that out, but with help from a good mentor and from this book I've really tried to shift away from getting involved directly, as hard as that is sometimes.

To begin with, you need to understand what help you're being asked for. For any professional disagreements what's really being said is, "Please help me get better at working with this person." This can be true, even if they don't phrase it this way.

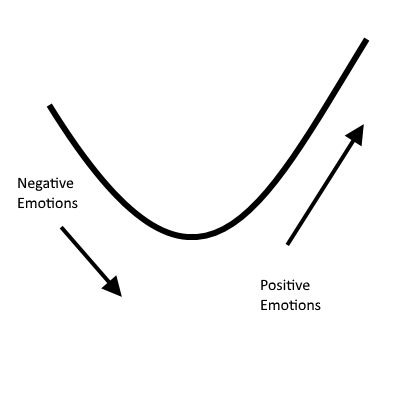

If someone is venting, you need to listen and ask why they're venting. Questions like - "What's really bothering you?" or "How do you think the situation could be resolved?" Can help them move away from their vent and focus on what they can actually do about it.

Once they begin to focus on problem solving for themselves, you can coach them through that - again questions are useful. "What else?" or "Do you want to rehearse what you will say?" are valuable here.

If they plan to talk to the person they're having a disagreement with, you should state your expectations for the interaction, “You’re going to speak to Ted this week? Let me know on Monday how it went.”, “Please listen to the other side of the argument and seek out a win/win.” Only get involved further if the sides seem unwilling or unable to reach a decision.

One other possible resolution strategy that I have used is to simply invite the other party to the meeting where the venting or other discussion is occurring. If someone is complaining or struggling with a workplace conflict, simply ask to bring the other party in. Then pick up the phone and say to the other party, "Can you come down here? I need your help resolving something."

Once both people are together I usually speak first and try to characterize the issue as I see it. Then the parties need to work together resolving a solution. This has the advantage of bringing both sides to the table and drawing forth quick resolutions.

You should be careful about when and how you employ this strategy and the different profession and emotional levels of the parties involved. It's effective if you feel the parties need supervision or if you simply want to make it clear that you want an answer now. It avoids all he said she said aspects. For manager-to-manager disputes or director-to-director level professional disagreements it can be an effective tool.

Most of the time, the two sides, when brought to the table in this fashion will see the expedience in working together to find the right solution.

There may be situations where you need to make the final decision. In that case, you make the decision.

In general I would still characterize this as a win/win to both sides if you can reasonably do so. But the 'loser' may not feel that way. Avoid overselling it. You can come across as dishonest if you don't realize that one of your employees just lost an argument.

Above all, you should make sure they know that you listened and that you appreciate their cooperation, you know they're a professional and will abide by the decision. Do your best to explain the business rationale of why you chose the way that you did. Avoid the urge to let them feel like they are owed one. In the future you need the latitude to continue to make the right business decision, based on who has made the best case.